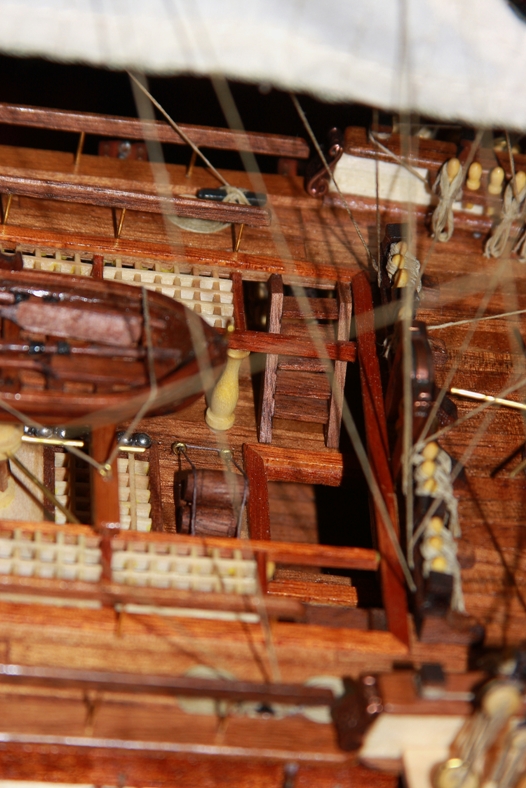

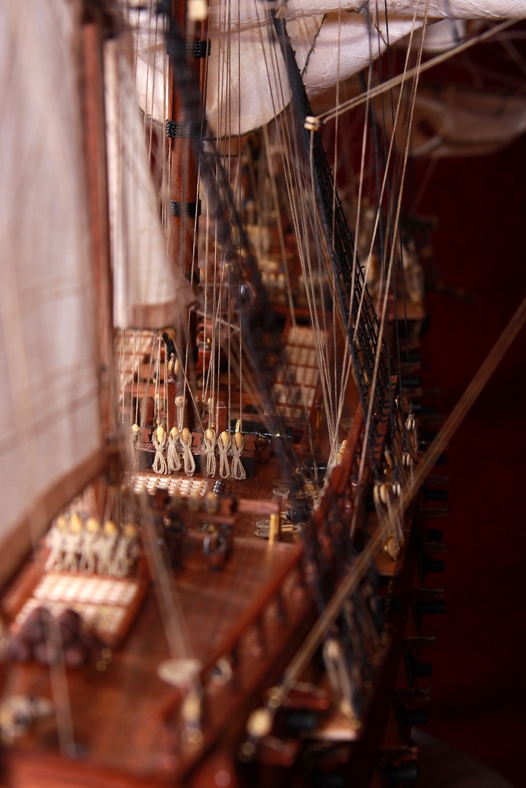

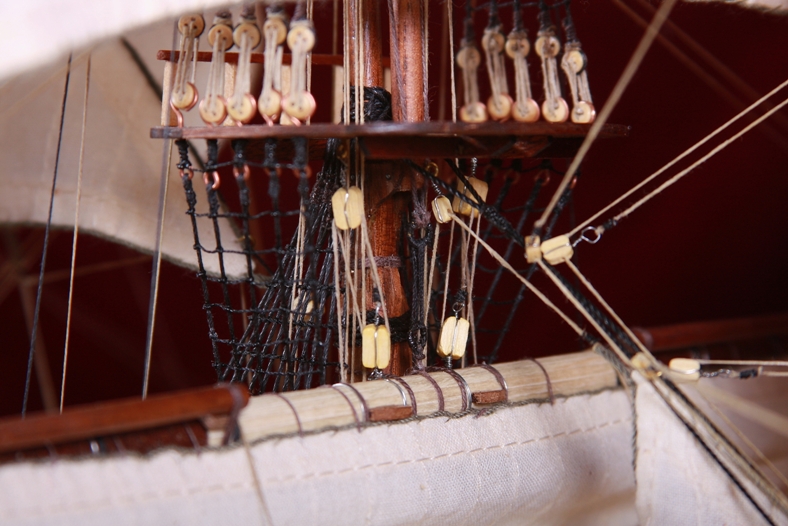

The deck fittings of a vessel can make or break a good model. Planking and building a vessel can be an arduous and tedious task. I like to take a break with what I’m doing and work on the deck fixtures and details of the ship.

The life boats of a ship prior to 1600 were not only able to be rowed, but also often included a single mast to fit a sail. As documented in Colubus’ notes, this was the case with his vessel. In one area of Columbus’ notes, he writes about a time in which he brought one of his longboats onto the poop deck and adjusted the sails.

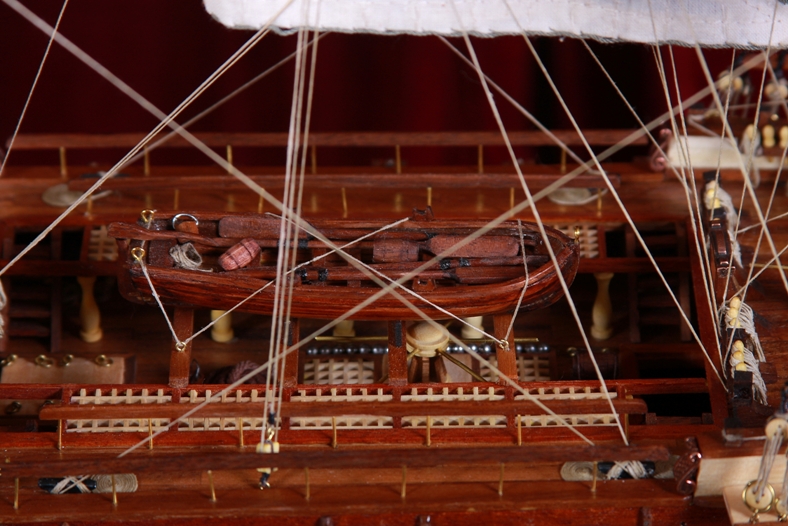

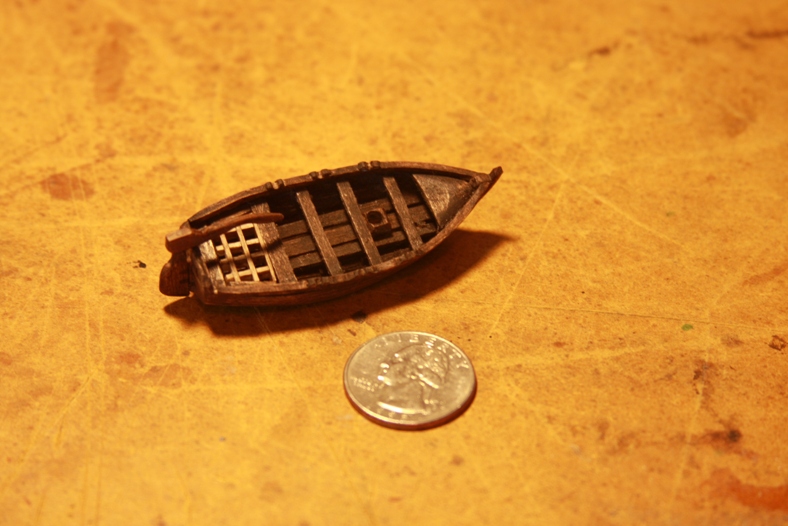

The “lifeboat” that came with this kit was a die cast pewter model that lacked any kind of detail. So I set about creating a suitable craft to go aboard the ship.

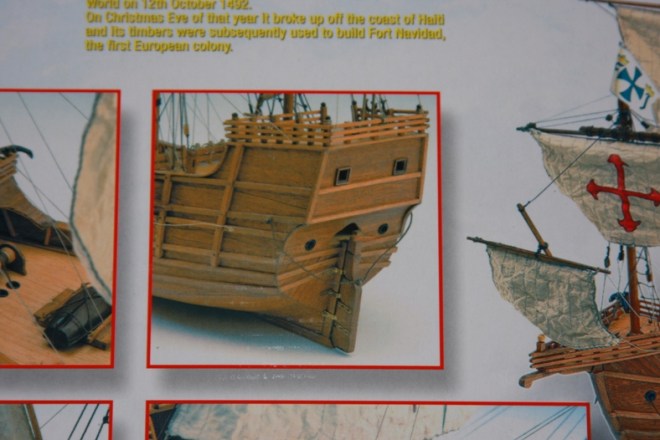

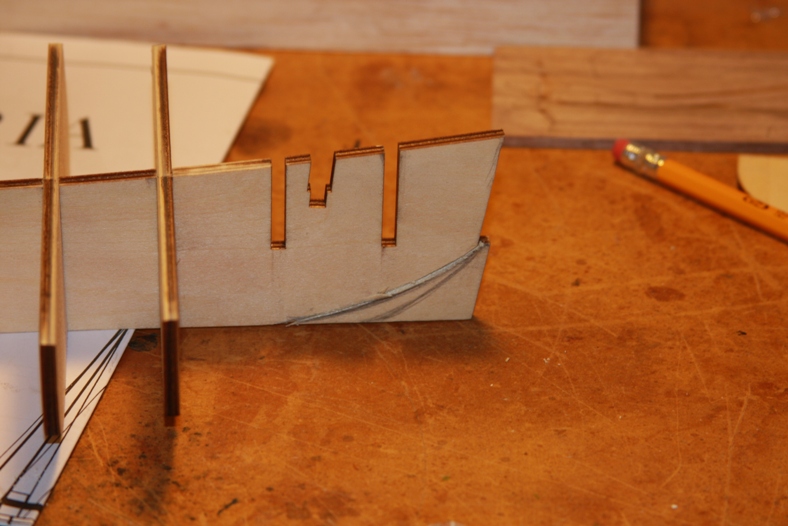

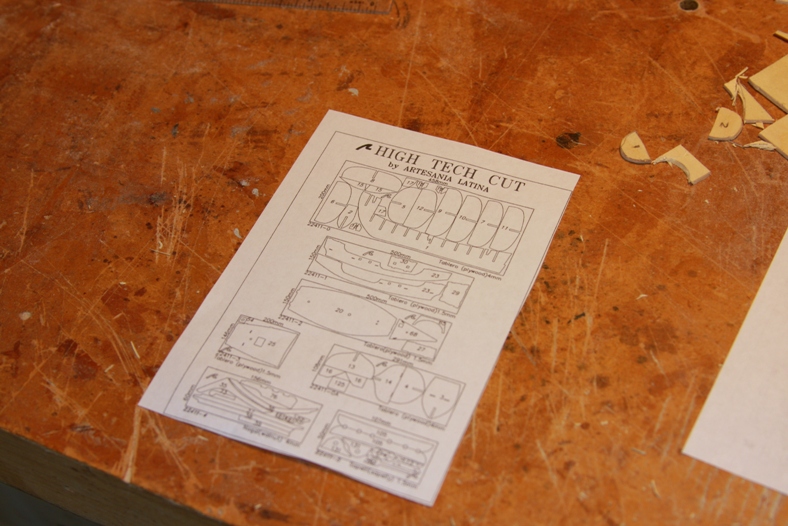

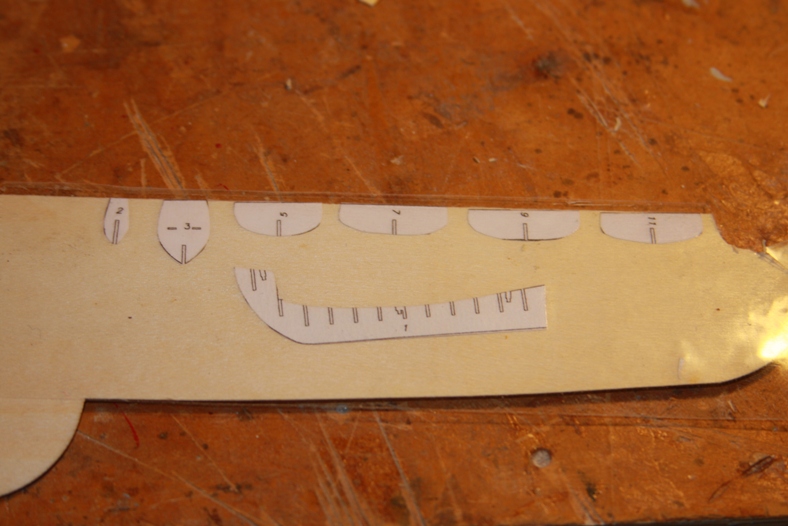

It occurred to me, that the lifeboats from the era were essentially the same shape as the overall vessel. I decided to take the diagram of the parts list that came with the kit and shrink it down on my copier. I could then cut out those pieces and use them to manufacture my little craft.

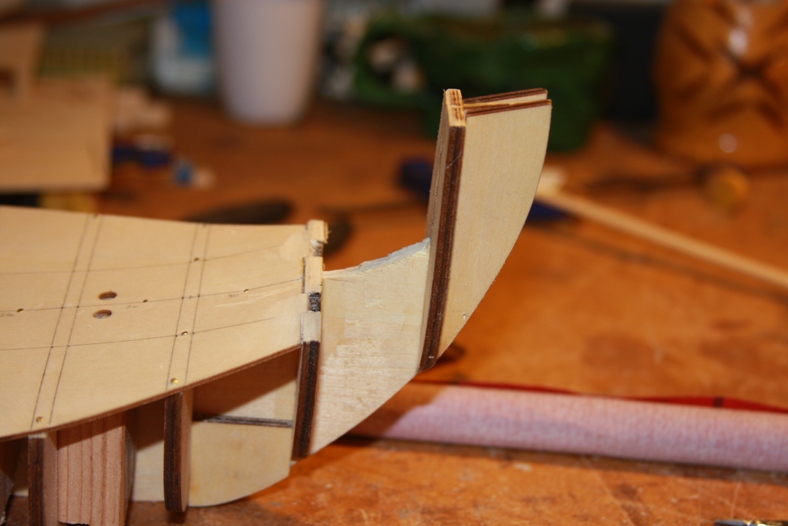

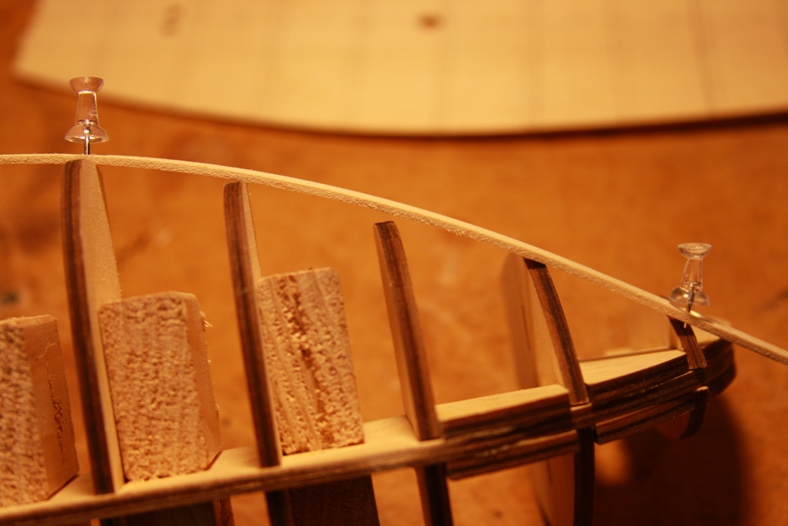

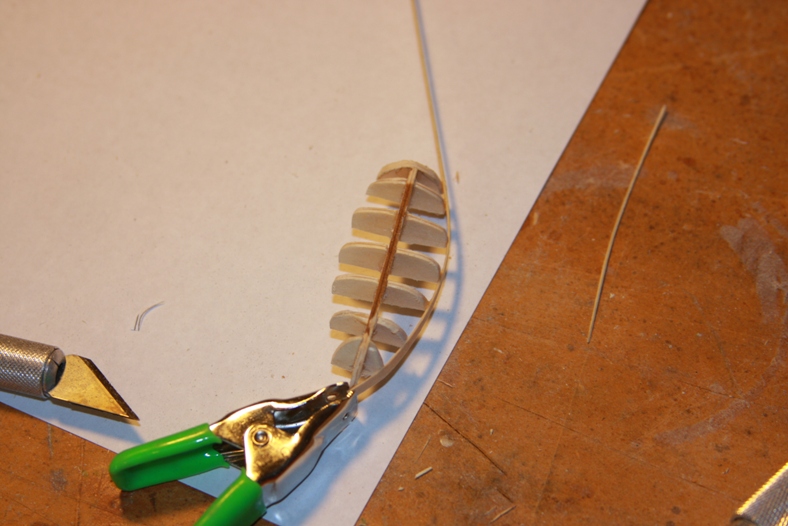

After cutting the pieces out and attaching the mini bulwarks to the keel I used thin spare wood to plank my tiny hull. I then took my dremel too with a rounded sander and shaved down the bulwarks and turn them into a proper frame.

After the first layer of planking, I figured out that shaping the hull with a boat this tiny was extremely difficult. I decided to double plank. Although this is obviously twice as much work – it will give me an opportunity to even out the hull and make it look smoother.

The other ships I have built have been very “clean” and often look as though then just came from the shipyard. This is the first time I will have attempted to “weather” and ship and make it look “antique” and “worn”. This lifeboat gave me an opportunity to try out couple things out.

I gave the boat a base with a cherry stain, then covered it with a darker, almost ebony dark oak stain. Then I sanded it lightly with 600 grain sandpaper. I originally tried just the darker stain, but after sanding, too much of the light color wood came through.

I will likely build one additional lifebat as a long boat to accompany this smaller skiff. As a frame of reference for time, this small vessel took approximately 20 hours start to finish.